Research and data visualisation

Early research

Old vs new data

Debate on the value of ‘old’ data - such as mine from the special collections - and ‘new’ data is a historical thing, albeit that, according to Menke and Schwarzenegger, “what is considered old or new is always relational because it depends on the individual and generational temporality of comparison, personal media ideology, and the situational circumstances" (2019, p.665).

As technology develops, and becomes generally more “appealing” (Menke and Schwarzenegger, 2019, p.658) the pair continue, we should not underestimate the value of ‘older’ datasets and reject “the rhetoric of the old” (Menke and Schwarzenegger, 2019, p.662) by which the novelty of newer media pushes for the extrusion of non-digitised data, for example. ‘Old’ data can be just as rich in value; and through analysis across time, I believe that we are therefore allowing ourselves to learn about the modern day thanks to ‘old data’ being considered as a comparator, and commonality.

Moving deeper

A good introduction to this project can also be found in video, accompanied by more in-depth literature based research beneath.

This project concerns three key areas: identity, dialect, and community ties. As the video explains, Identity is often considered a construction, and something that is incomplete (Hall, 1996). However, thinking of it as a static phenomenon can help “…to group people based on characteristics such as race, class, and gender, whether for demographic or political purposes,” (Marwick, 2013, p.356). This project leans into this by focusing on local community, yet I do recognise and acknowledge the multiplicity of identity and how it is also influenced intersectionally through factors such as race, class and gender (Turkle, 1999).

Robins says that identity can be related to not only individual matters, but also “collective”; it is “to do with the imagined sameness of a person or of a social group” (2005, p.110). To feel a sense of such collective identity, people might ‘perform’ in certain ways in order to conform to said group – invoking Goffman’s notion of performativity, which argues that we present ourselves as a performance to others in order to construct identity (1956). One of these ways can be a person’s use of language.

Language can vary depending on area, with varieties differing “on oral language parameters such as phonology, morphosyntax, and vocabulary” (Jarmulowicz et al., 2012, p.410). In the UK especially, certain words – dialectical terms - can be viewed as "markers" (Labov, 1972, p.178) which can position "groups into specific local and social circumstances" (Llamas, 2007, p.581). This then builds a “speech community” (Llamas, 2007, p.581) as although the notion of the “common dialect” (Wright, 2000, p.6) – received pronunciation – exists, Penhallurick and Willmott argue that this standard English "excludes the majority and, through a familiar twist, places the minority at the centre of normality” (2000, p.43).

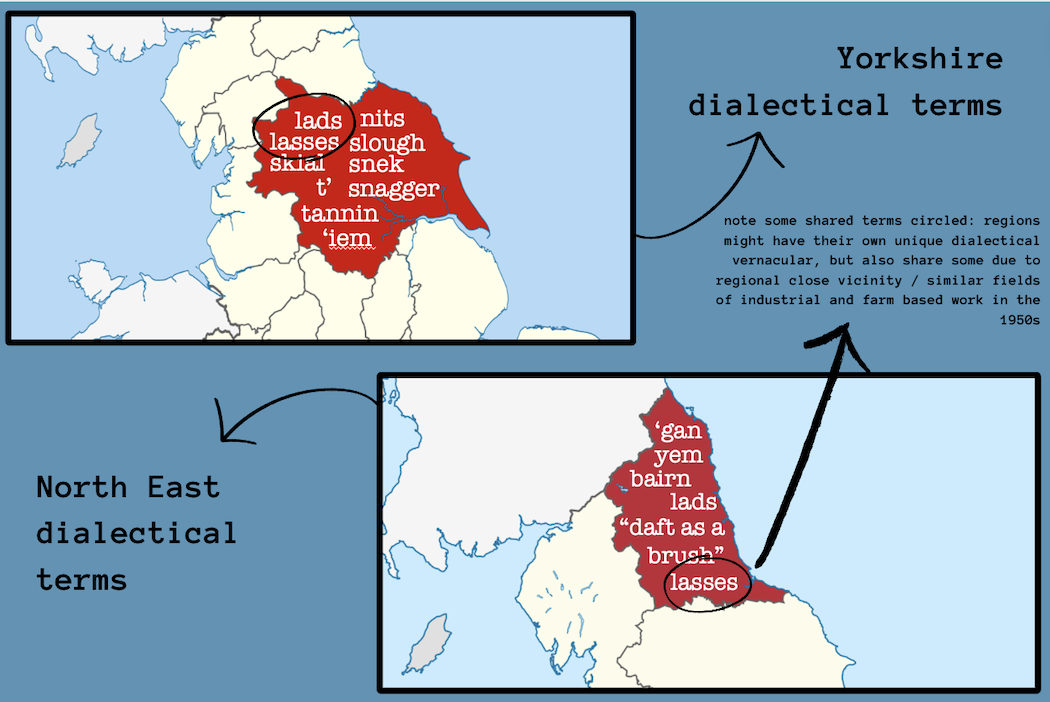

See below this example of playful cartographic mapping, with terms taken from my special collection that I have used as "markers" to position groups of people locally...

This method of data visualisation draws upon inspiration from The Playful Mapping Collective (2019) who emphasise the importance of play and experimentation within cartographic techniques. I also draw inspiration from mapping hobbyist Starkey Comics, who makes an important note which I acknowledge in the above graphic: that whilst regions within a similar area hold their own distinct words, "dialects do not suddenly change as you move from one region to another. They flow and merge over time in complex and messy ways, like coloured inks diffusing into water" (2023).

The North in general and its dialect has been the subject of discussion for some time. Ruano-Garcia speaks of the north as being perceived since medieval times as “alien and barbaric… which has largely influenced popular images about the North and the dialect” (2020, p.189). In turn, he continues, personality traits are associated with an accent, and a consequent “set of social and cultural attributes" (p.191), resulting in a sense of othering. The notion of othering can therefore result in potential strengthening of social identity – what Turner refers to as "a person's definition of self in terms some social group membership with the associated value connotations and emotional significance" (1999, p.8). Collective social identity can then result in the formation of community ties.

Referred to as “locally based social relationships beyond the household and family” (Horak and Vanhooren, 2023, p.3), community ties tap into what Castells refers to as the networked nature of society (1996). We are all involved in a community in some capacity, and one of those can be a local community. And, knowing this project focuses on two areas – Yorkshire, and the North East – Greenbaum’s 1982 study finding that "lower income groups are inevitably dependent on the maintenance of strong ties to kin and neighbors in order to withstand periodic crises” upon concentrating on a local community in America of similar lower socioeconomic status indicates a link between local area and identity.

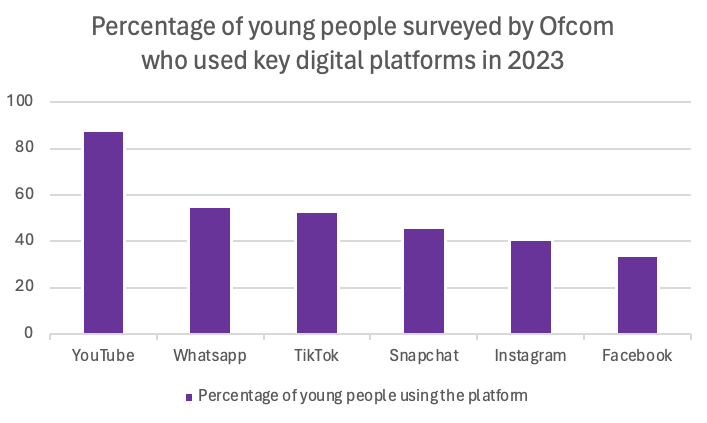

Interestingly, there has been utterances of disruption to community ties and networks; Castells argues that they have been "reconfigured" by technological change, allowing an expansion of social movement and in turn “entirely transforming sociability”. Social media, specifically, he notes as “disruptive” and causing “chaotic turbulence” (2023, pp.941-943).

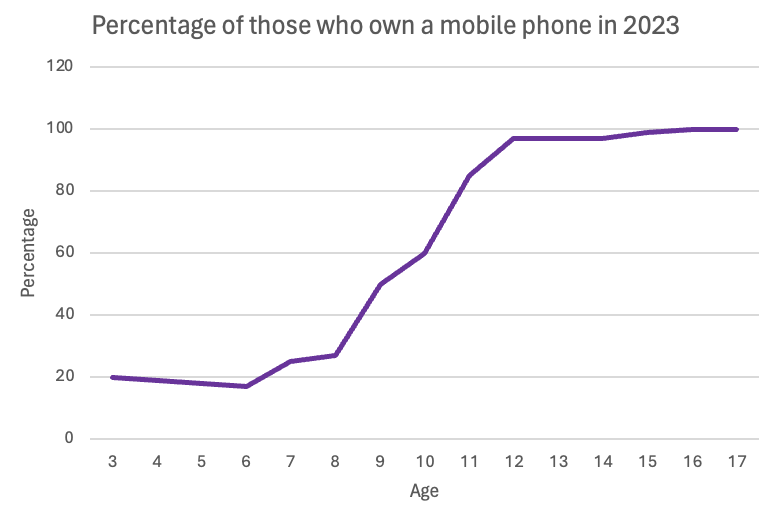

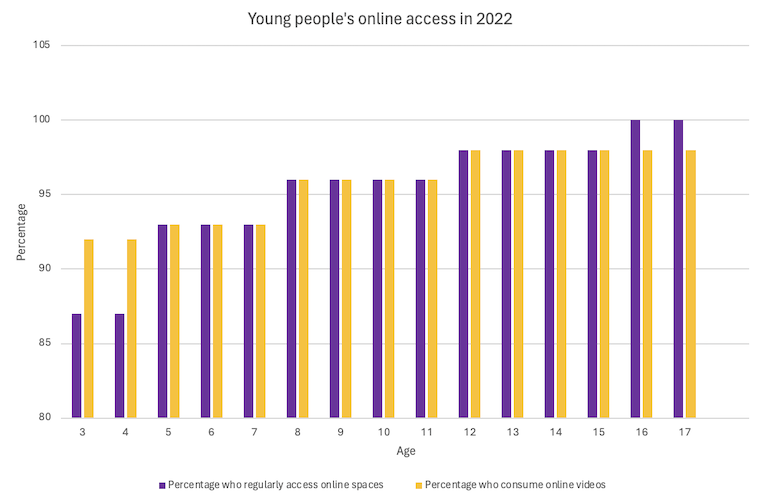

Perhaps Ofcom describe this best in their 2023 report, in which they note that when looking at the above in the context of youth, children owned mobile phones "gradually" up to age 8, "when the rate of ownership accelerates to levels that are near-universal among children aged 12" and beyond. Ofcom also suggests that in 2022, 97% of children 3-17 went online (2023, p.7).

Find these, amongst other interesting finds, visualised below:

Amidst this, Barbu et al. have simultaneously noted the ongoing disappearance of “regional languages” (2014). Pearce’s study, specific to the North East dialect, reported participants discussing a homogenisation of dialect (2009). Coined ‘dialect levelling’, interviewees said dialectical nuance is “dying out”, expressing their “sadness” at the fact (pp.185-186). Are there links here, perhaps, between people's social mobility being increased due to access to other worlds (see the below visualisation and note my anecdote in the introductory video) and consequently different ways of speaking online?

This body of research therefore suggests that there are links between language, identity and community ties, but also a simultaneous potential disruption to communities and homogenisation of language.

To explore the project’s creative output and some more visualisation, head here.

Reference list for this page (including video) here